Democratising in Design Part II : Attitudes of Implied Design Independence

“Anyone can design, if you have the right resources, materials, tools and people - you’ll get there in no time!”

I was first introduced to the term “democratising design” when I came across Herman Miller’s Eames Chair staged at the entrance at Lane Crawford. The setup presented a library of customisable parts, ranging from type of graphic for seat, type of finish and materials for the legs. The appeal of being able to create my very own Eames Chair was attractive. However, it was the excessive amount of prints that ranged from plane to flora that made me question on the necessity of the amount of choices, as it started to resemble an Ikea furniture assemblage the longer I examined the design.

“Democratising design” can be interpreted and perceived in many areas and can hold a positive or negative light depending on the context. In the context I was introduced in, “democratising design” is framed from the rise of mass self-customisation and the ease of accessibility to design tools (3D printers, iPad Pro and the beautiful Apple Pencil). The user-friendly interface of these tools combined with providing a suite of parts for the audience to construct their own custom design now gives majority a chance of ‘design’, hence democratising the process of design. Arguably, it can be seen as playing on the psychology of giving the user a sense of intimacy with the design subject. It’s a simple yet very effective marking idea considering it allows people to have a sense of creative independence. The ability to have control in creating your design is indeed a beautiful thought, however, potentially detrimental to the future of designers. As the market becomes saturated with the kit-of-parts-esque design, it risks affecting the audiences’ mentality and arguably attitude towards designers as well.

Coming from a cultural background that traditionally (and dare I say stereotypically) frowns upon the world of design, it is understandable to foresee a snowball effect of perceiving design as a simple field. Moreover, it can affect our design reputation in a positive or negative light – depending on whether the audience are willing to understand the depth and detail of various design disciplines.

From the rising trend of renovation shows, and the amount of DIY channels on Youtube, because of the apparent accessibility and resources it is very easy to leave an impression of “if I can do it, so can you”. This type of manner of thinking has been applied frequently in the sharing economy businesses (Task Rabbit, Air Tasker, AirBnB, Uber, etc.). Which while is beneficial for those who are seeking alternatives for economical solutions, is detrimental to other business specialties. Further, from the designers’ angle, the providence of “choose your own” type businesses and design solutions can also lead to a similar effect as the sharing economy, due to the straightforwardness of the design solution, could potentially deter audience should they eventually become involved with the complexities of the design.

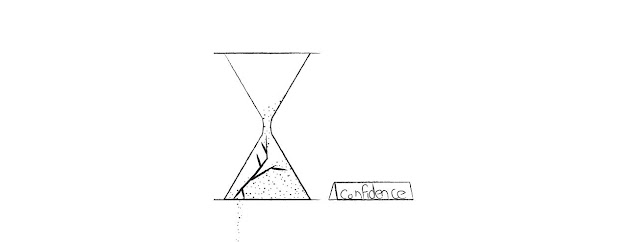

Customisation of design can arguably arise from our habit of searching for the aesthetic in visual as well as the attitudes of wanting to follow the trend yet with discretion and dignity. This is similar to the idea of purchasing counterfeit goods we often see in the markets – it is giving the people a sense of belonging and confidence now that they have owned a part of the trend.

Although, taking lessons from Johanna Blakely’s talk on free culture from fashion design we can safely say that customisation and appropriation occurs mainly because:

1. Prevent the chances of people saying that they have out right ripped off someone else’s design

2. For owners to have their own ‘customised’ design relatively original, one-of-a-kind despite being bought off a template

Architectural wise, the rise of customisation has existed for some time now. It is fair to say that there has been benefits for those who may have been overwhelmed by the procedure to achieve their dream architecture thus turn to Small Home Services, plans provided by home builders. Furthermore, with the possibility of having templates generated by coding is already another sign of customisation in architecture - another type of democracy in design that is accessible for the market. For instance, with parametric design and coding becoming a common language in almost any industry, it could be easy for one to assume that designing architecture would simply be based off from coding.

Albeit, I am hopeful that the conflict of democratisation in design is a hurdle that we as designers will be able to overcome. Understanding that there are still documentaries (thank you Grand Designs) that highlights the difficulties and challenges of various design disciplines means that we are acting on the perceived assumption on the ease of design. This is also a good opportunity for us to open conversations about the communities of design, and for us to collaborate effectively together to tackle and work with the rising trend on taking measures to ensure that users are having accessibility to ‘good’ design.

More importantly, we also need to collaborate and discuss with those who are outside of the design discipline – educating them about the areas that would give respect to the process of design, that way we can minimise the superficial mentality of assuming the straightforwardness of design.

This is one angle of “democratising design” that we could examine, however - given that the terminology is rather broad itself, we need to understand the flip side and perhaps the identity of the term “design” itself.

Democratising in Design Series: Part I, Part II

References:

- “Chapter 2 – Democratising Design: The Rise of Mass Customisation” – IMAGINE, SPACE10, 28 June 2017

- “The Democratization of Design” – Medium.com, Joshua Taylor, 25 March 2016

- “The democratization of design” - TED x Leeds Lecture, presented by Clive Grinyer, 7 October 2009

- “Lessons from fashion’s free culture” - TED x USC, Johanna Blakley, April 2010

- “Democratising Design - Making New Futures by Breaking Old Rules” - University of Sydney, Panel discussion with Katja Forbes (Founder & Managing Director at syfte), Mathew Aitchinson (Chair of Innovation in Applied Design, University of Sydney), Martin Tomitsch (Head of Design, University of Sydney), Tim Horton (Registrar, NSW Architects Registration Board), Selena Griffith (Senior Lecturer, UNSW Engineering Manager, Scientia Education Experience), 13 September, 2016

Comments

Post a Comment