You Speak What?

“Being in this studio, you’ll come to realise (through interaction with architects and non-architects and your friends) that … as communication of languages are constantly changed and intertwined with each other there is always a way to come through with what we want to express, let alone it is also a never ending search of the universal language that can make everyone understand what we’re trying to say without having to reinterpret it… But as always, being unanimous doesn’t really comply in the field of languages.”

- Communicating Architecture Folio, 2016

Ah languages. I always have fun teasing my friends and my father in particular when I start combining Cantonese, Mandarin, Japanese and English in a conversation (this happens too when I become stressed or alone). It becomes more entertaining for me when to my dismay, I unconsciously start talking about the buildings surrounding me, which to some of my family and friends, I am speaking another foreign language to them again.

At the beginning of my third year in architecture, I was fortunate enough to be in a studio which remains till this day by far my favourite. My studio tutor Evie Blackman challenged us to decipher the meanings hidden behind selected architectural theories and designs. It proved to be a challenge at first considering that my analytical skills were not the strongest. Let alone, it was taking the concept and applying it to another medium that made it difficult. Nevertheless, I was engrossed in understanding how these creators were able to manifest their thinking within different media, which eventually led to us being boldly questioned whether architecture was necessarily defined in the absolute built form. In developing that question, we were put to attention about how what we learn becomes a different language itself.

It is arguably hard to completely decipher what each person’s language truly despite given the context. To complicate matters, it is the communicating process between two perspectives (or sometimes three) that makes the final outcome either weak or strong. No matter what the artist say or write, eventually the audience who look at their work would subconsciously apply connotations to the artwork in order to make it more relatable for themselves. How I know this? I’ve had the honour of listening to a lady enthusiastically pointing to each of the objects in my installation and explaining their meaning to me before I could give a proper answer. Though it was taxing at times, it was better than having several people coming up to me to enquire my other installation - which made me feel somewhat defeated considering that no one picked up the story behind my installation.

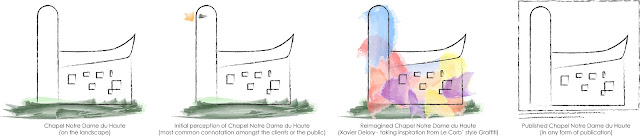

Assumptions, connotations and denotations work at their finest when the person finds what they see foreign. For instance, Le Corbusier’s process of designing Notre-Dame du Haut (also known as the Ronchamp Chapel) was met with mixed reactions, we have people re-imagining it as the nun’s cowl, to a pair of hands, a duck and my personal nickname for the unconventional building - a mushroom. However, despite the range of puzzling criticisms the unusual church was still erected, and still stands as one of the most important precedents today. Let’s not forget, after the completion of the Sydney Opera House; from a group of turtles lumped on top of each other like they were preparing for mating season to the opening of a strange flower - the public’s opinion of the arts centre’s facade was rather a cocktail of comical descriptions. I can’t conclude whether the mixed bag of reactions are defeating or a source of motivational boost for us designers to make our own language become fully comprehensive. After all, each individual experience events differently that it becomes a reflection of their character.

|

| Notre-Dame du Haute Representations |

Which brings me to Venturi and Brown’s “The Duck and the Decorated Shed” theory. At what point do we need to make our building evidently obvious that audience do not need to question what the exterior building is trying to reflect for the interior? Otherwise, do we need the interior looking so heavily saturated with elements for the visitors to have a grasp of the program within? Picture yourself walking down an empty street, and you come across a row of buildings that all look identical yet unbeknownst to you, the activities within each building are different. Would you then proceed to open each door and peep through the windows to determine which building you would like to enter in? Or would you simply assume that the buildings all have the same activity and continue walking in hopes of finding the building that has a large sign that tells you that this is where you need to be? Shamefully I admit that I might have chosen the second option, simply because of the fear of being impolite for barging my way into each building to understand what is going on. Perhaps then, it is because of how we have been brought up and because what we have been taught that has led us to always seek for signs that would help us navigate to the correct direction.

Then, if interpretations are simply a collective of individual’s experiences then would that be the reason why architects are often quite reserved in giving the full explanation of their concept of their building? I’m quite positive that there are many reasons why there are a lack of experience. Sometimes, I’d like to believe that it is because that would allow people to have discussions about the architecture that they designed - in that sense it would allow them to accomplish something. Since I am quite an idealistic individual, perhaps having people attempt to understand my building would then allow me to recognise that my work at least allows people to think about their surroundings, thus perhaps prompt them to venture and explore what is happening.

With that being said, we then need to consider that this strange field of languages and communication is a complex matter. Ever since I entered architecture, I started speaking a different language that does not apply or overlaps with the everyday context. I have had a few run ins with my close audiences, with my mother in particular - we once nearly had an argument of how I should leave out the cross out in the title font since it would confuse my audience when in my own world it made perfect sense to me. Nonetheless, the application of words with various terms that led to a huge confusion when it comes down me attempting to explain the meaning of my work to my parents. This has happened to me too many times where my own ideas get the best of me. My most unfortunate attempt - my communication poster where while I thought explained the concept of “building on top of the dead” combined with “more dead than the living” was beautifully done on my poster. Nope.

|

| Nope. They don't see how we're building on top of the dead or on top of the girl. (Comm Project back in 2014. Building Projects: Le Corbusier's Villa Savoye and Veronica Arco's Casadetodos. Precedent: Jordan Munns, Long After I'm Gone 2011) |

It can become quite frustrating really, being a student sitting in a laboratory of experiments and trying to figure out the best way of allowing architects and non-architects to grasp your ideas. There will be plenty of ups and downs, yet I guess which is why architecture is being publicised and expressed in various media. Whether it’d be the physical form, photograph, text or sounds, prototypes are constantly made in order for us to be confident in what we design.

Yet, let’s not forget that this applies to every occupation, field, culture and individual as well.

Comments

Post a Comment